Thoughts on the length of scenes

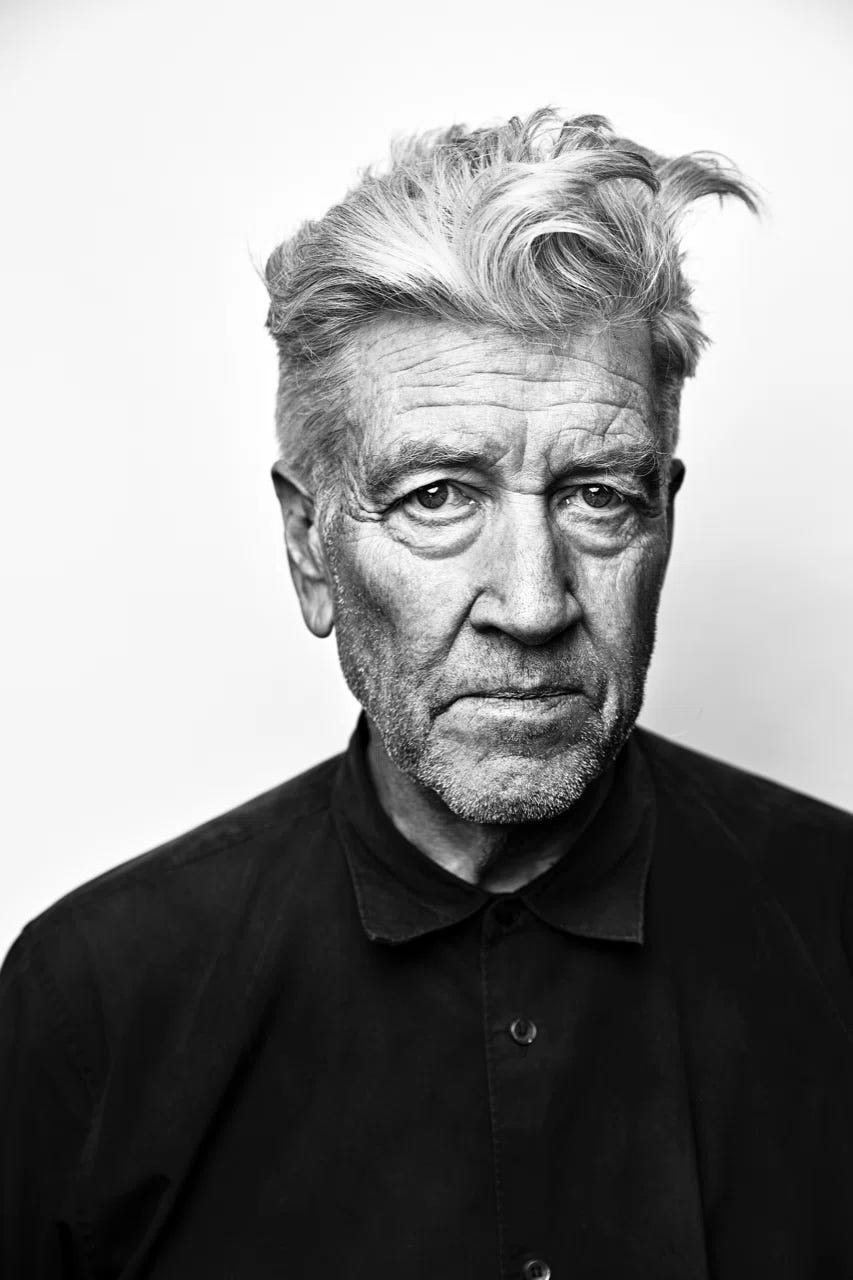

The other day I came across a clip of David Lynch on the set of Twin Peaks: The Return (2017). In it, his producer suggests they cut down the time of the scene they are filming. Lynch is apoplectic. “What is this with everybody? What is this? I’m serious! Fuckin’ a man, it drives me nuts! Who gives a fucking shit how long a scene is?”

I’ve been on a Lynch kick recently, watching a bunch of his movies I haven’t seen, including Eraserhead (1977), The Elephant Man (1980), Dune (1984), Wild at Heart (1990), The Straight Story (1999), and Inland Empire (2006), as well as rewatching Blue Velvet (1986) and Mulholland Drive (2001). I rewatched Twin Peaks season 1, which I had seen years ago, and am working on season 2, which I have not seen, with the goal of completing it, Twin Peaks: The Return and Fire Walk with Me (1992) to become a Lynch completist. His is arguably the best director to watch clips of on Youtube, having willingly turned himself into an internet meme of sorts. When I came across the above clip, it immediately struck a chord with me, and I have been thinking about it for days.

To answer Lynch’s question, most filmgoers are concerned with length. Mainstream cinema is all about pace: editing is complimented for being “tight”, scenes are expected to further either character or plot, and filmmakers are taught to “kill their darlings” in the editing phase, which is something William Faulkner supposedly said. I recently watched Jeremy Saulnier’s new Netflix film Rebel Ridge and thought it was an exemplary case of tight editing and a focused narrative, without an ounce of fat on it. I was thrilled from beginning to end and immediately texted a friend: “Rebel Ridge is the most purely satisfying experience I’ve had with a film in awhile.” If Saulnier had let any one scene drag on for too long, the whole edifice of the movie might have collapsed.

Lynch is of course a different case. “Propulsive” is not a word anyone has ever used to describe any of his films, though phrases such as “dull as dishwater” and “interminably boring” have been used by critics (in both cases referencing Inland Empire). Even his hit-murder mystery tv show (Twin Peaks) occasionally moves at a glacial pace.

Take the first scene of season two: we open on FBI Agent Dale Cooper lying in his hotel room after being shot by a mysterious assailant in the final scene of season one. A bald, elderly hotel clerk, donning a red bowtie, slowly walks into the room with a glass of milk and says “Room service!” to a man who is lying in a puddle of his own blood. The clerk moves in closer and says “How are you doing down there?” to an apparently unconscious Cooper. Cooper lightly opens his eyes and turns his head but does not speak. The clerk says “Warm milk!” in a chipper tone, and Cooper tells him to put the milk on the table and call a doctor. The clerk makes a scene of hanging up Cooper’s phone, on which a colleague is trying to speak to him on the other side, and is then reminded by Cooper to call a doctor before cheerfully announcing he will do just that. But before he does, he gets Cooper to sign a bill for the warm milk, then exits the room painfully slowly, occasionally turning to smile at Cooper before finally leaving.

Just when we think this interminable scene is over, the old clerk comes back into the room to tell Cooper, “I’ve heard about you!” and give him a thumbs up, to which Cooper gives a thumbs up back. The clerk slowly leaves the room again, before abruptly turning around and coming back in to give Cooper a wink, another thumbs up, and a second wink, before leaving again.

At this point the scene has been going on for over 5 minutes. This is how Lynch chose to open the highly anticipated second season of his hit show to 19.1 million American viewers in 1990: with a weird old guy in a red bowtie waddling around a hotel room with a warm glass of milk while our protagonist threatens to bleed to death. I have no idea why the scene is this long, but I do know that it’s pure David Lynch: no other director in cinema or television history would have ever thought to execute this scene this particular way. It has all the Lynch elements: the juxtaposition of the brutal (gunshot wound) with the innocent (a glass of warm milk), the cheeky optimism of strangers, the denial of traditional narrative pacing. Some accuse Lynch of performative weirdness, or “weird for weird’s sake”, but I think that Lynch mostly just puts what comes to his head to the screen without intellectualizing it, even though there’s surely a part of him that relishes pulling his audience’s leg a bit.

Some filmmakers push the limits of how long a scene can be way further than Lynch. One of the most famous examples would be Béla Tarr’s Sátántangó (1994), a 7 hour and 19 minute adaptation of a 300 page novel (I can confirm that it’s faster to read the book than watch the film). The film opens with a 10-minute long tracking shot of cows standing around a muddy field, setting the tone for the remaining 7 hours and 9 minutes of black-and-white, rural Hungarian hell. Then there’s Jeanne Dielman (1975), Chantal Akerman’s 3.5 hour magnum opus that is mostly a Belgian woman doing house chores. The latter was voted the greatest film of all time in the 2022 edition of Sight and Sound’s once-every-decade list, voted on by directors and critics (Sátántangó came in at #78).

Few dare to suggest that Sátántangó should be, say, 10 minutes shorter. How would you even “trim” a movie where the enormity of its length is the entire point? Would the movie be better if the cow scene was only 5 minutes long? There’s probably a universe where Béla Tarr could have made a 6 hour version of the film, but that’s not what he did, so we get what we get. I took an experimental film class in college where the teacher screened a film (the name of which eludes me) that was around 90 minutes of repeated, loosely-connected images, completely lacking any discernible narrative. It was very much a “vibes” movie: you’re either on its wavelength or not. A student argued afterwards that the film could be half as long and would lose nothing. The teacher snapped at him, claiming definitively that there was no problem with the length and that the problem was in fact with our generation because of our pathetic attention spans.

I think the teacher was right but for the wrong reasons. Blaming our generation for criticizing a weird art film that does indeed feel very long is misplaced; would boomers all be united in hailing the film as a masterpiece? I think there isn’t any problem with the length because that’s the film the director made, and if he had a made a film half as long I would have probably thought the same thing. One’s response to this type of film will vary, but the “what if the film were this” game feels inappropriate for an experimental film of this nature.

When it comes to narrative-driven films, though, I certainly can find fault with length. I’m in the camp that thinks that Martin Scorsese’s Killers of the Flower Moon (2023) would have been a much better film if it were an hour shorter. This film’s length caused an uproar amongst cinephiles online, most of whom chided the average moviegoer for complaining about the length and hailed the film as a masterpiece. At the same length as Jeanne Dielman, Killers certainly has more going on than a woman peeling potatoes. But the film feels like it doesn’t understand what type of movie it is trying to be, droning on without any real momentum or narrative cohesion. Scorsese can obviously do what he wants, and I’m enormously grateful he is still making ambitious films, but for once I side with the common man in my frustration with a film’s epic runtime.

With Lynch’s films, unlike Scorsese’s, narrative momentum is usually beside the point. Ultimately, with Lynch, we get what we get. There’s no version of Twin Peaks where the hotel clerk only waddles around with a glass of milk for 2 minutes. Does Mullholland Drive absolutely need the scene where the guy from Lost comically murders a few random people in order to steal a book of phone numbers, a scene that bears absolutely no relevance to the rest of the plot and which is never brought up again? Yes, because it made sense to David Lynch to have that scene in that place, and it works within the greater tapestry of the film for reasons that are hard to articulate.

Of course, someone like Lynch gets the benefit of the doubt more than a lesser known filmmaker would because he’s an icon. But I think this line of thinking can and should extend to all films. Filmmakers like Lynch, Tarr and Akerman are trying to recondition how we watch film and television, an antidote to the way our expectations have been dictated by mainstream media. What good is art for if it doesn’t shake us out our comfort zones a bit, awaken us to the world around us instead of acting as a narcotic? Who gives a fucking shit how long a scene is?