The Filmic Language of the Future: The Work of Jane Schoenbrun

Most films are fairly forgettable: we see them, we enjoy them or don’t, then we move on with our lives, and within a few weeks the film is a distant memory. Sometimes I love a film as I’m watching it and assume it’s going to stay with me over the subsequent weeks, months, and maybe even years only to find that it melts into thin air as quickly as an episode of The Great British Bake Off. Case in point: I saw Sean Baker’s new rapturously received film Anora a month ago and enjoyed it a quite a bit, suspecting it might be one I’d chew on for some time to come, but alas, it has sifted into the mental ether (unlike Baker’s The Florida Project, which I still think about not infrequently).

I saw Jane Schoenbrun’s second feature I Saw the TV Glow during its limited release in May, knowing virtually nothing about Schoenbrun or the film. It had an immediate impact, though I wasn’t quite sure what I had watched. In the Lettboxd review I logged immediately afterwards I noted, "Not sure the whole film hangs together perfectly but it made an impression.” Over the past 6 months, I have thought about I Saw the TV Glow more than a bit, and certainly a hell of a lot more than any other new film I have seen this year. It has proven itself to be what I will henceforth refer to as a “noggin film”: a film that you just can’t get out of your cranium. Sometimes noggin films are ones that I disliked or outright hated on first viewing that slowly grew in my estimation over time (examples of this for me are Mulholland Drive and Sorry to Bother You). Other times, it’s films like I Saw the TV Glow that I cautiously liked, only to have that caution disintegrate, replaced by a passionate embrace.

I finally got around a couple days ago to watching Schoenbrun’s first feature, We’re All Going to the World’s Fair (2021), followed by a rewatch of I Saw the TV Glow, and I am now fully convinced that Schoenbrun is a major new voice in American independent cinema. As our digital lives grow more complex, many filmmakers are retreating to the past, avoiding trying to discern how to tell a compelling visual story about people immersed in screens. For context, here are the most recent films by some big name directors that are set in the present day:

Paul Thomas Anderson: Punch Drunk Love (2002)

Steven Spielberg: War of the Worlds (2005)

Martin Scorcese: The Departed (2006)

Quentin Tarantino: Death Proof (2007)

Wes Anderson: The Darjeeling Limited (2007)

The Coen Brothers: Burn After Reading (2008)

I don’t think it’s an accident that the release of the iPhone in 2007 coincides with the death of history as depicted by mainstream, “high-brow” filmmakers. I can’t really fault these directors for sidestepping the digital world altogether, though at times the larger cultural trend feels a bit cowardly. Thankfully, some up-and-coming filmmakers are facing our fractured world head on, and none more compellingly than Jane Schoenbrun.

We’re All Going to the World’s Fair is set in the present day in a nondescript, cold suburban town littered with recognizable corporate signifiers (Toys’R’Us, Best Buy, etc). The physical world is basically an afterthought, though, since we spend practically all our time with teenager Casey (Anna Cobb) on her computer in the house she shares with her father, who we never see. The extended opening shot positions us looking at Casey from right above her computer screen as she records a video of herself completing the “World’s Fair Challenge,” a viral horror-themed challenge which involves her drawing blood from her fingertip, wiping blood on her computer screen, and watching a strobe-light video with strange audio cues. We soon learn that this ritual is supposed to destabilize the life of the participant, and Casey vows to record updates of herself to demonstrate the changes she experiences (to her single-digit number of followers).

Casey does occasionally walk around her neighborhood while filming herself, but we never see a single other human. School is never mentioned. She doesn’t appear to have any friends, or human connections of any stripe. She begins to feel off-kilter and consoles herself by watching ASMR videos made by Youtubers that help viewers calm down after a nightmare. Casey presents as definitively non-feminine, and the way she talks about the change inside of her suggests a young person questioning their gender, though this is never explicitly addressed (Schoenbrun is transfeminine). Casey also watches videos of others participating in the World’s Fair Challenge: some claim they can no longer feel their own body, are developing inexplicable rashes, etc. It’s unclear at first how seriously we are supposed to take all of this: is this all a game? Does Casey understand that these other people are role-playing, or does she think this is all real? Schoenbrun incorporates many tricks to destabilize the viewer: occasionally the whole screen turns into a loading bar, which roughly correlates to when Casey is loading another Youtube video, but for someone watching the film on a laptop (as I was), the effect is uncanny. Did my internet just bug out? Is this a film, or some weird internet voyeurism I just stumbled into? Is there a meaningful difference?

One person who expresses concern over Casey’s increasingly unhinged videos is an internet user who goes by “JLB” and who we initially see only through an avatar as he has a Skype conversation with Casey, telling her he is worried that she is getting absorbed by the powers of “the fair” (there’s a lot of lore surrounding this whole World’s Fair business). He presses Casey to keep making videos so that he knows she’s ok, and when their conversation ends, we cut to JLB in the flesh, a middle-aged man living seemingly by himself in a McMansion. And what, exactly, is this lonely, older man doing obsessively watching videos of a disturbed teenager spiraling out of control? Schoenbrun provides no answers to this question, leaving the audience to decide for themselves. What does come across is that internet alienation is not specific to any age or class: JLB is middle-aged and rich, Casey is young and seems to be fairly poor, and both are equally lonely.

I won’t summarize the rest of the movie, but suffice to say that Casey’s connection to reality only grows more tenuous, leading to musings on harming either her father or herself, and one wishes they could scream through the screen to help get her mental health support. We don’t know what ultimately happens to Casey, though JLB does tell a story to his Youtube followers about meeting her in-person after she received professional treatment. Due to his interest in role-playing games, though, we have been primed to distrust JLB: is he telling the truth, or has he concocted a fiction that satisfies his need for closure over the fate of an at-risk young woman he briefly had contact with? I would bet on the latter, but Schoenbrun wisely leaves the matter unsettled.

While I Saw the TV Glow is a period piece mostly set in the 1990’s, it feels just as modern as We’re All Going to the World’s Fair. Instead of the internet, Schoenbrun focuses their sights on television, the way the glowing box gives meaning to our lives. High school freshman Owen (Justice Smith) is just as alienated as Casey: he has no friends, overbearing parents, and seems deeply uncomfortable in his own skin. This being the pre-internet era, though, Owen does not have the same outlets that Casey has. Instead, he seeks comfort in the subversive, young adult tv show The Pink Opaque, a sendup of 90’s Nick at Nite programs like Are you Afraid of the Dark? as well as Buffy the Vampire Slayer. The problem is, The Pink Opaque airs at 10:30pm on Saturday nights, and Owen isn’t allowed to stay up that late. His solution: sneaking out of the house to watch the show with high school junior Mady (Brigette Lundy-Paine), the fiery queer girl who turned him onto the show.

When Owen expresses his interest in watching The Pink Opaque with Mady, she’s initially a tad suspicious. “I like girls, you know that, right?” she asks. Owen nervously assures her he’s not interested in her sexually, and when she tries to deduce whether he likes girls or boys, Owen is deeply uncomfortable. “I…I think I like TV shows,” he replies. This is our first glimpse at how out of touch Owen is with himself. It’s not a matter of a teenager questioning if he’s gay: Owen simply refuses to ask any questions at all. Owen follows this up by telling Mady about the emptiness inside of him: “When I think about that stuff, it feels like someone took a shovel and dug out all my insides. I know there’s nothing in there, but I’m still too nervous to open myself up and check.” Owen will do anything to deflect difficult questions about who he really is, suggesting that he is suffering from gender dysphoria.

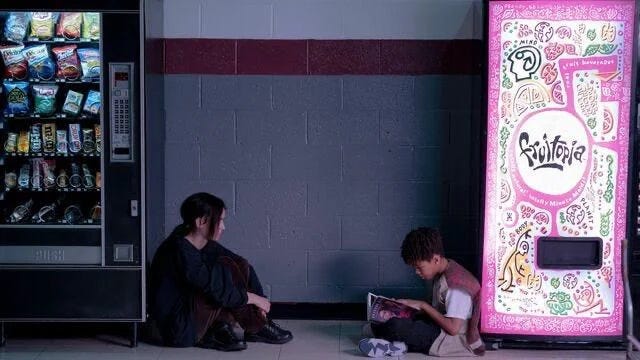

Schoenbrun knows how to visually convey these themes rather than simply stating them outright, and this scene with Mady is a good example. Earlier in the film, when a younger Owen first encounters Mady, Schoenbrun positions them between two vending machines:

Mady, dressed in dark clothes, sits next to a black, dimly lit vending machine, while Owen, in lighter clothes, is next to a bright, pink, “fruitopia” machine. Fruitopia may be a bit on the nose, but we get the point: Mady has excised all femininity from herself, while Owen may have some latent, undetected femininity inside of him. This same color motif returns during the aforementioned scene between the two:

Mady is rocking a colorless tank; Owen a pink sweater. These two are in many respects an odd couple: Mady understands herself and her sexuality, but she is trapped in an unhappy existence with an abusive stepfather. For her, The Pink Opaque, a show about two young women (Isabel and Tara) who are telekinetically linked and fight monsters, speaks to a reality she would like to escape into, leaving her shitty world behind. For Owen, The Pink Opaque is an opiate: it speaks to something profound about himself, but he is not interested in investigating what that is. Instead, he wants the drip to continue so that he can delay self-examination for as long as possible.

Speaking of colors, Schoenbrun evokes different forms of glow throughout the film. Most notable is the way pink is reflected from the TV when Owen and Mady watch The Pink Opaque, even though when we see the show, the amount of pink represented is minimal:

This is not motivated lighting, but it’s not purely stylish, either. Instead, Schoenbrun is suggesting that something is off about the reality that Owen and Mady inhabit: it’s not quite real, you could say.

This sense of unreality is made literal later in the film when Mady, after having disappeared for eight years without a trace, returns to town with some shocking news for Owen: she entered the actual show The Pink Opaque and discovered that her and Owen are in fact the two leads of the show. This crappy world they think they inhabit is in fact a ruse, a distraction to hide them from the truth of their existence. Mady is the badass Tara, Owen is the sensitive Isabel, and they have supernatural abilities waiting to be unlocked. Mady/Tara tells Owen/Isabel (now referring to him simply as Isabel) that they have to perform a ritual in order to return to their true existences and defeat the primary villain of the show, Mr. Melancholy, who has created this melancholic alternate universe to keep his foes at bay. At Mady’s behest, Owen goes home and re-watches the final episode of The Pink Opaque, which has long been off the air. As he watches, the truth of Mady’s words becomes clear to him, and as the credits roll, he has a breakdown that results in him sticking his head inside of the TV. As his father runs into the room and tries to help him, Owen begins shrieking things like “This isn’t my house!” and “You’re not my father!” Schoenbrun has described the film as exploring the “egg crack” moment, which is when a trans person crosses the rubicon of understanding who they are, which does not correlate to their assigned gender. This is that moment for Owen. Everything about his life until this point has been a lie.

*Related tangent/rant: in virtually every piece I have read about I Saw the TV Glow, critics refer to the film as an “allegory” about the transgender experience. I have long been annoyed at film critics for misunderstanding what an allegory is, and this is a prime example. Owen is a woman, he (she) is Isabel. This is the text of the film; there’s nothing allegorical about it. During Mady’s monologue about their true selves, we see images of Owen in a dress, posing for Mady. Of course, the film has a supernatural bent to how it portrays the trans experience, but that doesn’t make it “allegorical.” Animal Farm is an allegory because the farm animals are stand-ins for figures from Russian history; we understand that since pigs and boars don’t actually politically organize themselves that Orwell is asking us to think about human systems. Allegory can work in literature because there is an imaginative aspect to the written word that does not exist in film. Film is in many ways a very literal medium. The image is objective; we all experience it the same way. When someone reads a book, however, they take part in imagining what the author describes, which is unique from how any one other person imagines those details.

When filmmakers actually do try allegory, it usually fails spectacularly. To cite a particularly egregious example, Darren Aronofsky published a statement following the release of his film Mother! (2017) that definitively claimed that the film, which is ostensibly about a small dinner party that increasingly spirals out of control until the house has been destroyed and many people are dead, is actually about climate change and how humans have despoiled the only planet we have (the house is the earth, and the guest are the humans, but Jennifer Lawrence is Mother Earth, I think, and Javier Bardem is God, oh and there are literally characters named Cain and Abel, and…nevermind). The film itself is thuddingly obvious in its references, but the allegory also fails because all we see is people tearing down a house and abusing Jennifer Lawrence. It is not easy to watch a film and think “oh, this woman is supposed to be Mother Earth” and mentally replace the two in the same way one can do while reading. Film is immediate; it is ill positioned for metaphor. That Aronofsky felt the need to publish a statement explaining all this is insulting and evidence that he knows that the film on its own fails to convey what he was going for. Directors: let us do the work ourselves, God dammit! End rant.

Rather than embracing this new discovery, Owen does everything in his power to put the genie back in the bottle. He abandons Mady when she tries to get him to return to the real world and never sees her again. Years later, we see that Owen is living the same, dull, lonely existence he always has, only now he’s older and frailer. He’s still working dead end jobs, now at an entertainment center (think Chuck E. Cheese). His hair is greying, and his lips are astonishingly chapped. He hobbles around like he’s an octogenarian, though the timeline suggests he’s in his 40’s. He tells the camera at one point that he has a family that he loves very much, but we never see them, and it’s possible they don’t exist. Owen has successfully kept the truth of his identity at bay, but at a massive cost to his well being. He wheezes audibly as he walks around, a painful thing to watch.

In the final scene, while working a kid’s birthday party, Owen suddenly starts screaming uncontrollably, rolling on the floor while claiming he is dying and asking for his mom. Schoenbrun stages this so that everyone else in the scene freezes still during Owen’s freakout, showing how invisible Owen’s suffering is to those around him. He goes into the bathroom with a box cutter and cuts his stomach open to finally see what’s inside himself. He pulls back his stomach flaps (which make a vaginal shape) to find a TV inside, playing The Pink Opaque. Owen smiles for basically the first time in the whole movie, and if Schoenbrun had ended the movie here, it could be seen as a hopeful ending. Owen finally faced what was inside of him, and it was The Pink Opaque, as Mady had suggested. But no: we get one more shot of Owen walking back through the entertainment center, meekly apologizing to the patrons that he disturbed with his freakout. Virtually nobody is paying attention to him; everyone has moved on, and Owen seems ready to move on too. What could have been a revelation leading towards a different path appears to be foiled once again by Owen’s insistence on staying the course in his sad, lonely life. (This film obviously has zero chance at awards recognition, but in a just world, Justice Smith would be honored for his work, which is genuinely phenomenal. Too bad it lacks the flashy overacting that gets awarded).

Neither We’re All Going to the World’s Fair or I Saw the TV Glow end well for our primary characters. And yet, Schoenbrun’s films are a far cry from the melodramatic, fatally tragic trans and queer films that have dominated mainstream cinema (Boys Don’t Cry, The Danish Girl, etc). These are not “it gets better” films, because we see that things definitively do not get better for Owen. But that doesn’t mean he’s completely hopeless, as indicated by a chalk message we see on a street towards the end of the film that reads “There’s still time.” Coming out as queer or trans is a devastating and life-altering experience for anyone, especially a young person, and many delay the process for as long as possible; some avoid ever having an egg crack moment. Schoenbrun is charting the psychic toll that denial takes on a person, which feels like a more honest and humane way to portray the trans experience than a phony story of triumph and uplift (though there’s of course room for more hopeful stories too). And while both of these films are about the trans experience, they speak to anyone who has ever felt alienated and uncertain about the reality they inhabit (this is another thing I see heterosexual/cisgender critics say that irks me, “I can’t connect to the queer/trans experience, so I won’t comment on that.” Like, have you tried? Seems to me that attempting to understand while acknowledging your barriers to entry is always the best course of action).

I recently saw Harmony Korine’s debut film Gummo (1997) for the first time, and before the screening the theater played some clips of a very young Korine talking to Werner Herzog about the film (Herzog was both an inspiration to Korine and an early admirer of his films). “When you look at the history of film, from Griffith to where we are now, I see so little progression,” Korine opines. “I wanted to create a new viewing experience…I wanted to make a new kind of movie.” Korine has receded into obscurity in recent years, but thankfully we have Jane Schoenburn carrying the torch, creating new kinds of movies to help us make sense of our rapidly changing world. As a friend of mine wrote on Letterboxd, “Jane Schoenbrun speaks the filmic language of the future.”